The Count of Monte Cristo, Illustrated

The Count of Monte Cristo, Illustrated Knight of Maison-Rouge

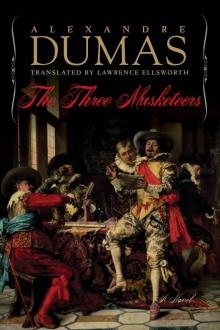

Knight of Maison-Rouge![The Three Musketeers - Alexandre Dumas - [Full Version] - (ANNOTATED) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/14/the_three_musketeers_-_alexandre_dumas_-_[full_version]_-_annotated_preview.jpg) The Three Musketeers - Alexandre Dumas - [Full Version] - (ANNOTATED)

The Three Musketeers - Alexandre Dumas - [Full Version] - (ANNOTATED) The Man in the Iron Mask

The Man in the Iron Mask The Count of Monte Cristo (Penguin Classics eBook)

The Count of Monte Cristo (Penguin Classics eBook) Count of Monte Cristo (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Count of Monte Cristo (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Women's War

The Women's War La reine Margot. English

La reine Margot. English The Vicomte de Bragelonne

The Vicomte de Bragelonne__english_preview.jpg) La dame aux camélias (Novel). English

La dame aux camélias (Novel). English The Count of Monte Cristo

The Count of Monte Cristo Balsamo, the Magician; or, The Memoirs of a Physician

Balsamo, the Magician; or, The Memoirs of a Physician Ten Years Later

Ten Years Later The Romance of Violette

The Romance of Violette The Mesmerist's Victim

The Mesmerist's Victim Vingt ans après. English

Vingt ans après. English Le collier de la reine. English

Le collier de la reine. English Taking the Bastile; Or, Pitou the Peasant

Taking the Bastile; Or, Pitou the Peasant The Hero of the People: A Historical Romance of Love, Liberty and Loyalty

The Hero of the People: A Historical Romance of Love, Liberty and Loyalty Louise de la Valliere

Louise de la Valliere Les Quarante-cinq. English

Les Quarante-cinq. English Ange Pitou (Volume 1)

Ange Pitou (Volume 1) The Royal Life Guard; or, the flight of the royal family.

The Royal Life Guard; or, the flight of the royal family. Les trois mousquetaires. English

Les trois mousquetaires. English Une fille du régent. English

Une fille du régent. English The Knight of Maison-Rouge

The Knight of Maison-Rouge The Count of Monte Cristo (Unabridged Penguin)

The Count of Monte Cristo (Unabridged Penguin) Ange Pitou

Ange Pitou The Romance of Violette (vintage erotica)

The Romance of Violette (vintage erotica) The Three Musketeers

The Three Musketeers Three Musketeers (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Three Musketeers (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Georges

Georges Man in the Iron Mask (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

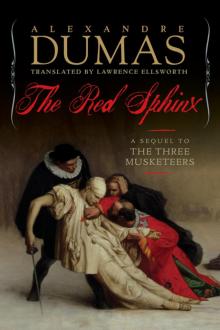

Man in the Iron Mask (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Red Sphinx

The Red Sphinx